English is the product of many cultures and despite being of Germanic origin, an important part of English language etymology finds its source in the French language. In Twenty Years After – the sequel to The Three Musketeers by French novelist Alexandre Dumas – D’Artagnan said “English is little more than badly pronounced French”. Several years later, George Clémenceau (early 20th century French PM) said the same. Is there any truth in their claim?

To find out, we need to go back in time and look at English language etymology in its historical context. But first, here are a few useful definitions.

English Language Etymology: Definitions

Cognates

Cognates are words that share a common ancestry. True cognates might not be instantly recognizable; they only share the same etymology. But they can also have the same spelling and meaning, or they can be loanwords or calques. They can be close cognates (same meaning but slight variation in spelling) and even false cognates (or “false friends” – same spelling but different meaning).

For example:

- True cognates: to attest < attester, from Latin ad-testari, curfew < couvre-feu, from the Old French cuevrefeu (used in the Middle Ages when fires had to be covered and people had to be home and off the streets by a certain time), coward < couard, Old French.

- Close cognates: analytique > analytical, créatif > creative, banque > bank.

- False friends: magasin (FR) = shop (EN) not magazine (publication), douche (FR) = shower (EN) not douche (EN) (medical term or type of person), bras (FR) = arm (EN) not bra (EN) (undergarment).

Read more about the etymology of words between French and English in this very interesting article http://faculty.uml.edu/jgarreau/fromfrenchtoenglish.htm.

Calques

Calques are words borrowed from another language and translated word for word. Calque is itself a loanword.

- Marché aux puces > flea market, point de vue > point of view, pomme d’Adam > Adam’s apple.

Loanwords

Loanwords are words adopted from another language without being translated, often with some modification of their form.

- Déjà vu, ragout, memoir, je ne sais quoi, cul-de-sac, crème brulée, carte blanche, faux pas.

Derivatives

Derivatives are words derived from other words or from a root in the same or another language.

- joie > joy, of which joyful (jovial) and joyous (joyeux) are derivatives.

English Language Etymology in its Historical Context

When did French words start to play a role in English language etymology?

The extensive borrowing of French words in the English language goes back as far as the 11th century.

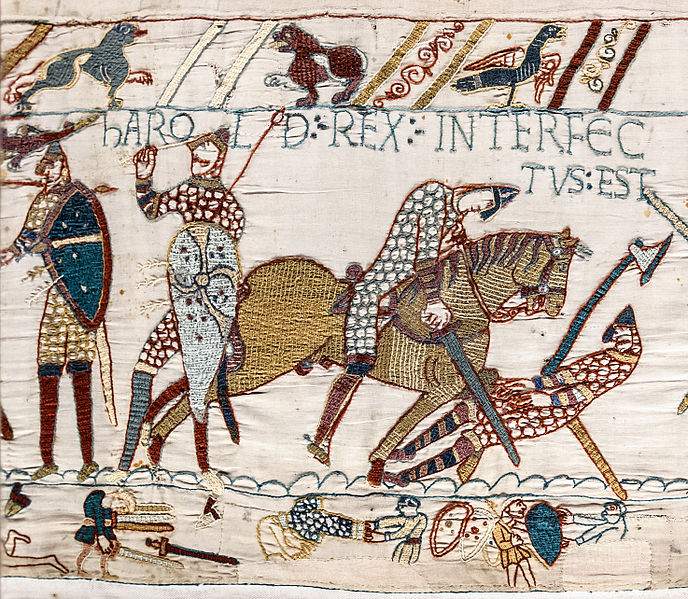

Following Edward the Confessor’s exile in Normandy in his early life, a few French words started to be introduced in the London court when he returned and became king in 1042. It was following the Norman Conquest of England (1066-1075) that the extensive borrowing started, and with the court under the influence of France, William the Conqueror – England’s first monarch – had an audience already receptive to the introduction of additional French words.

Over the next two centuries, waves of cognates and loanwords appeared in the domains of justice, religion and education. Some of the earliest borrowings from French are considered to be:

- Castle

- Prison

- Service

- Juggler

- Court

- Clerk

- Mercy

- Justice

- Grace

- Saint

- Sacrament

- Chaplain

- Purse

- Turn

- Trail

- Market

- Sot

- Mantle

French became the language of the aristocracy and English the one of the lower classes. Anyone who wanted to defend their property or personal rights, or gain an education, needed to know French to be able to communicate in the language of law-courts and schools. English was relegated to be used in the countryside rather than towns. It ceased to be used in literary writing, which suffered from a serious loss of vocabulary.

The 14th century – England’s traditional values regain the upper hand

By the second half of the 14th century, a strong, patriotic reaction gave rise to a revival of England’s traditional values and language. This period was also marked by a revival of English literary composition, with works from writers such as Wycliffe, Gower and Chaucer.

However, two centuries of borrowing had passed. This created deep roots and a predisposition to being receptive to words of similar forms. Even though English was re-established as the pleading language in law-courts by royal decree, French persisted in many ways through force of habit.

The 16th and 17th centuries – France’s limitless influence

Whilst the 16th century was permeated by Shakespearean English, it is also during this period that a striking number of French derivatives made their appearance. These have since become permanently fixed in the English language. Words such as:

| English word | Date | Definition | French word |

| Mimic | 1602 | Imitate someone’s actions / words | Mimique |

| Massacre | 1581 | Brutal slaughter of many people | Massacre |

| Sentinel | 1579 | Soldier who keeps watch | Sentinelle |

| Alexandrine | 1589 | Verse or line of 12 syllables | Alexandrin |

| Quatrain | 1585 | Poem of 4 lines | Quatrain |

| Gazette | 1605 | Newspaper or journal | Gazette |

| Belvedere | 1596 | Summer house with a view | Belvédère |

| Dessert | 1600 | Sweet course at the end of a meal | Dessert |

France was thriving in the 16th and 17th centuries and dominated in culture, art, literature, and the military, as well as political and social aspects. The Renaissance period of the 15th and 16th centuries symbolized change and innovation. France’s influence was limitless and unbounded, and took hold in England once more. This was no doubt facilitated by the fact that Charles II had spent nine years in exile in France before becoming king in 1660. Here are a few examples:

| Field | English word | Date | French word |

| Military | Commandant | 1687 | Commandant |

| Corps | 1711 | Corps | |

| Platoon | 1637 | Peloton | |

| Literature | Memoir | 1673 | Mémoire |

| Critique | 1702 | Critique | |

| Art | Contrast | 1695 | Contraste |

| Retouch | 1685 | Retoucher | |

| Profile | 1656 | Profil | |

| Miniature | 1645 | Miniature | |

| Serenade | 1656 | Sérénade | |

| Symphony | 1665 | Symphonie | |

| Elegance | Caprice | 1667 | Caprice |

| Intrigue | 1656 | Intrigue | |

| Beau | 1687 | Beau | |

| Brunette | 1713 | Brunette | |

| Fashion and Cuisine | Ragout | 1664 | Ragoût |

| Cravat | 1656 | Cravate (Tie) | |

| Pantaloons | 1661 | Pantalons (Trousers) |

Many of these words have survived and continue to be used daily in the English language, which – given the ephemeral nature of language – is very impressive and shows how deeply rooted they are.

The 18th and 19th centuries – England asserts itself

In the 18th and 19th centuries, a period of real expansion started and London became the centre of influence. The 19th century was a time of creations and improvements thanks to the age of industrialisation, transformations that permeated but also unsettled people’s minds and habits. By the end of the century, England was the world’s foremost imperial power, which asserted its independence from France.

England came into a new period of literary composition – the modernist literature – characterized by the radical changes of the rapid and unregulated industrialisation, and the First World War. Experimentation and the rejection of traditional ways of writing started, with writers turning against conventions and inventing new ones. Irish writers like Samuel Beckett and James Joyce both settled in Paris. Influenced by René Descartes – a French thinker – Beckett wrote in French in a very eloquent style, bringing more language diversity.

French in English Language Etymology Today…

Seven centuries later, phrases like Le Roy le veult (‘The King wills it’), now La Reyne le veult (‘The Queen wills it’), is a Norman French phrase still used in Parliament to signify that a public bill has received royal assent from the monarch. When a bill goes to the House of Lords for their approval, the words Soit baillé aux Seigneurs (‘Let it be sent to the Lords’) are written at the start of the bill. And when approving finance bills for Royal Assent, the Clerk says La Reyne, remerciant Ses bons Subjects, accepte leur Benevolence, et ainsi le veult (‘The Queen, thanking her good subjects, accepts their benevolence, and so wills it.’)

According to different sources, 45% of all English words have a French origin. Many native speakers recognize French words in English when they see them, but few know their true origins. With some 80,000 words making up the list of English words of French origin, language diversity is such that the majority go unnoticed. Having borrowings and derivatives in a language is an unavoidable and necessary process for a language to grow. There always comes a time when a language wants to expand and diversify. It generally coincides with a desire for change within the population of a country.

So, what about English words in the French language, I hear you ask? Well, that’s a topic for another post!

Contributor: Agnes Hawthorne

In the meantime, check out our other blog posts about Swedish and Spanish false friends!

If you are interested in language diversity and want to find out more about about the specific cultural characteristics of the English and French languages, check out our Localization Guides!